In November 2019, the world heard the word CORONAVIRUS, which a few months later became COVID-19. This disease is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus which was first discovered in China. From that moment on, the spread of this virus continued to increase. Indeed, the pandemic spread from country to country, and is now present almost everywhere. Millions of people have been infected and over four hundred thousand have died!

The pandemic and its rapid spread caused fear worldwide. Sanitary measures and other restrictions were quickly put in place in many countries. Among the decisions taken by government leaders, those relating to individual movement were the most significant. During lockdowns, individuals became confined to their homes, and schools, nurseries, universities, canteens, restaurants, shops (except essential ones), etc., were closed.

At this point, we ask the following question: did the implementation of these restrictions impact political sentiment? How has political sentiment changed over the course of the pandemic?

In this context, it is natural to wonder whether an alignment between political decisions and people's behaviour has been achieved. Have people felt that their leaders need to be more in touch with their concerns and are unable to address the challenges at hand effectively? Has the COVID-19 pandemic, with its restrictions on daily life, sparked a renewed interest in politics among the population? As we examine this dynamic, it is also important to consider the role of the leading political party. Have they received support from the population, or have they faced disapproval for their actions or lack thereof?

Is there alignment between political decisions and people's behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic?

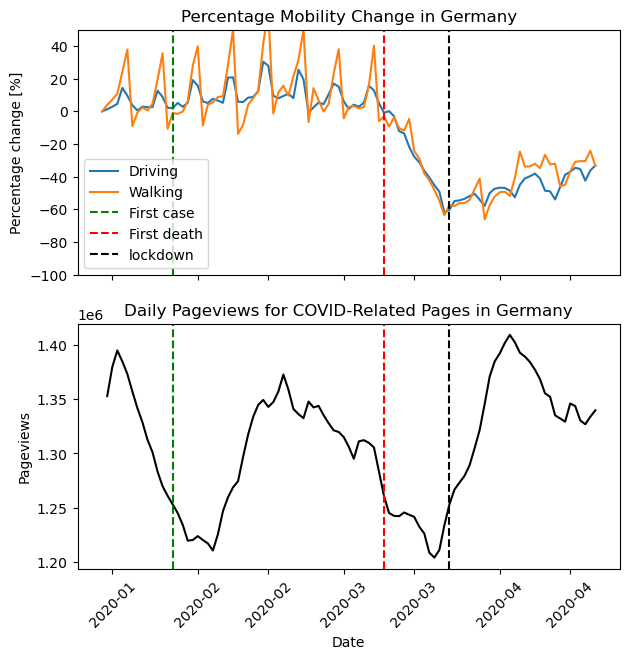

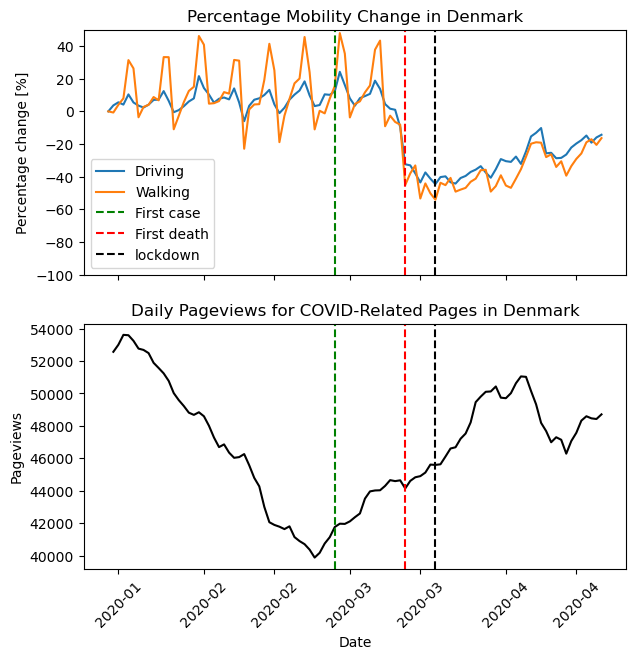

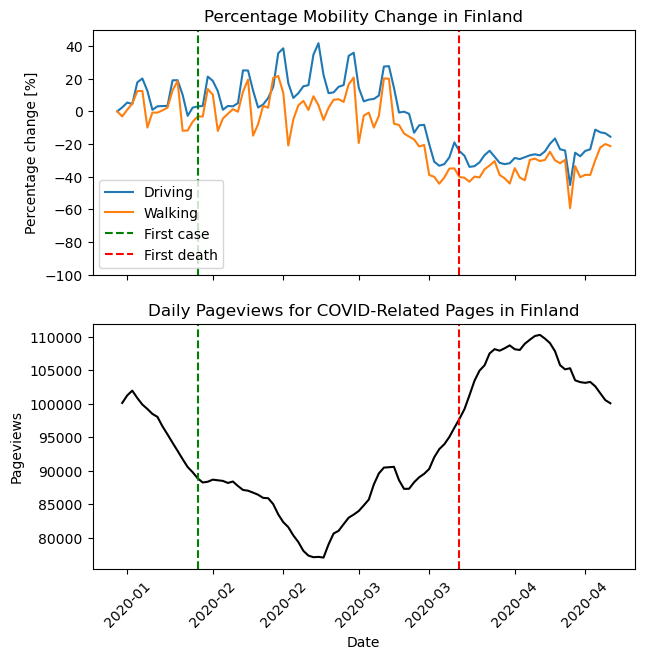

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented restrictions on mobility, forcing people to stay at home and go out only when necessary. But as the population adjusted to this new reality, a question lingered in the minds of many: who decided to reduce mobility? Was it the government responding to the crisis to slow the spread of the virus? Or were there other forces at play, shaping the decisions being made and dictating the course of the pandemic? The mobility data reveals an influence between the governments of European countries managing the crisis and their populations regarding reduced mobility. How European governments and populations responded to the COVID-19 crisis had a noticeable impact on mobility behaviour.

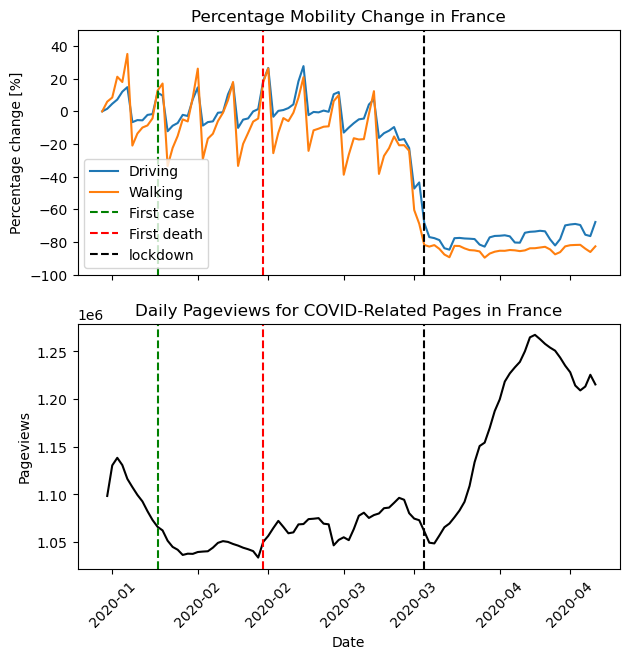

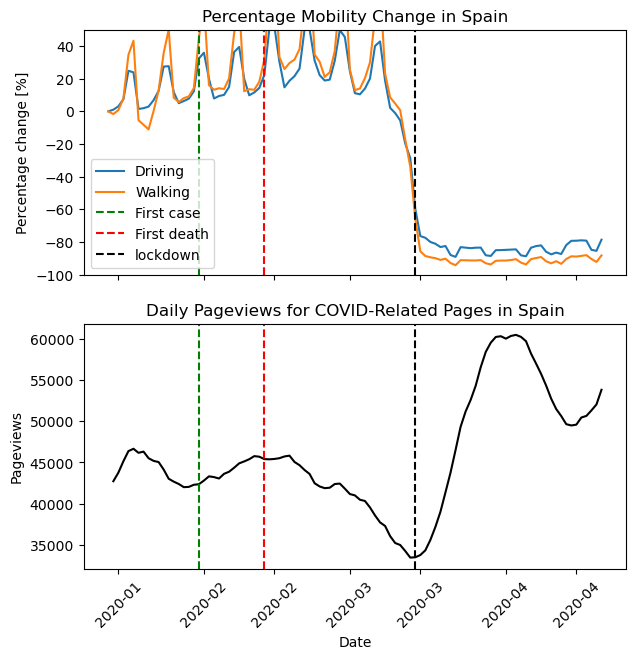

The graph below depicts the changes in mobility over time (don't forget to slide!).

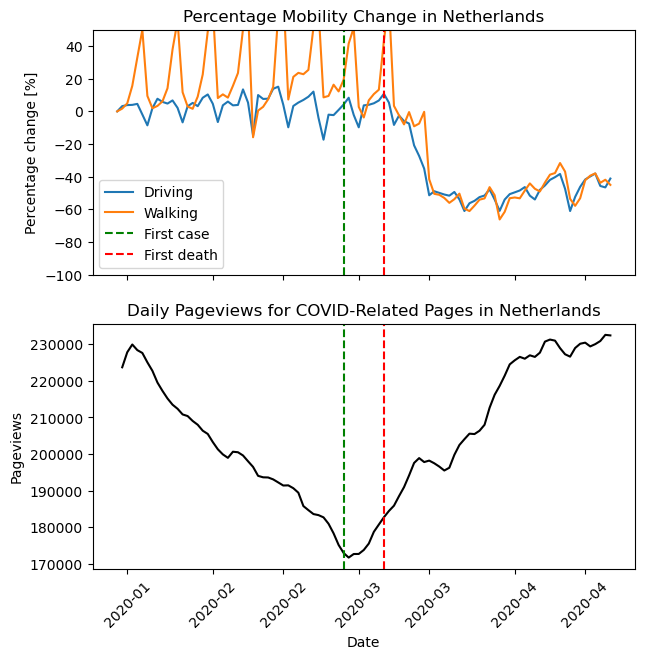

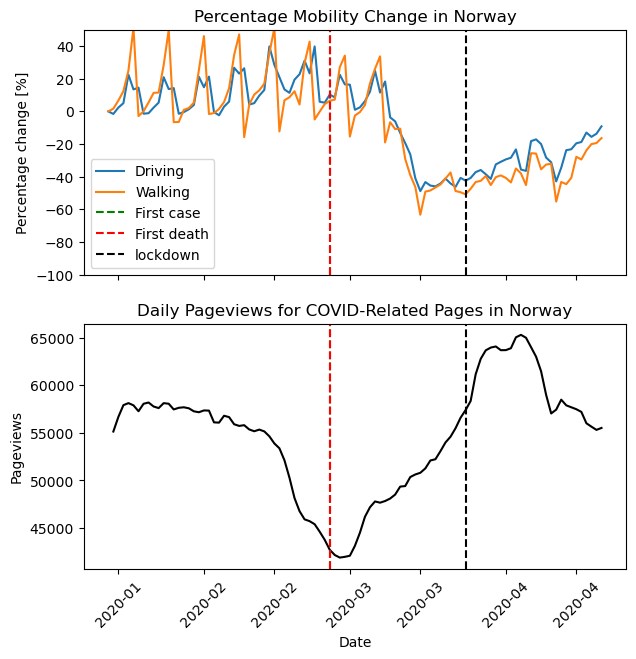

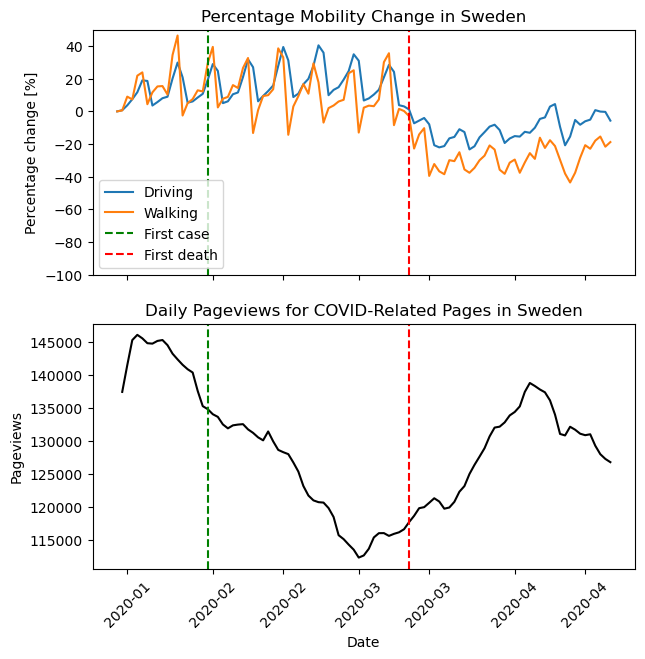

When the first deaths from COVID-19 occurred in countries such as France, Spain, and Norway, there was little change in mobility. This may be because COVID-19 was still relatively unknown in Europe then. However, as the virus spread more widely and began causing more deaths, particularly in countries like Italy, the interest in COVID-19 increased. This was reflected in the evolution of COVID-related pageviews over time. In Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Sweden, the first deaths were accompanied by reduced mobility and increased interest in COVID-19. In Denmark and Finland, where the first deaths occurred later, and events had already influenced the interest in COVID-19 in other countries, the increased interest in the virus likely explained the reduction in mobility.

Regarding what governments did concerning mobility behaviour, lockdown measures were often implemented once the decline in mobility had stabilised. This suggests that the government's restrictions on mobility came after the population had already decided to reduce their mobility. This may reflect a need for governments to be more responsive to the needs and concerns of their citizens.

As the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe, governments worldwide faced the daunting task of trying to ease the burden on hospitals and protect their populations. To this end, many governments implemented various measures, including confinement, school closures, and mask mandates.

But as the crisis wore on, it became clear that not all countries were acting similarly. Some countries were more aggressive in their efforts to control the spread of the virus, while others were laxer in their approach. This raised the question: are there countries that acted similarly, or were they taking a unique approach to the crisis?

Is it possible to group countries based on their reaction time to the crisis?

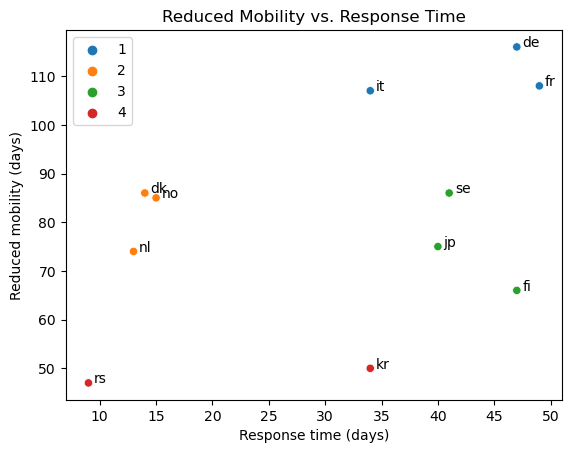

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed a wide range of differences in how countries have responded to the crisis. By analysing each country's reaction time – the length of time it took for the first measures to be imposed after the first case was detected – and the duration of mobility restrictions, we can try to group countries into clusters based on their response to the pandemic.

One group of countries that stands out is the "big European economies" – France, Germany, and Italy – which took a long time to react to COVID-19 and ended up imposing long periods of reduced mobility. These countries may have hesitated to take drastic measures due to concerns about the economy or the challenges of enforcing measures over a large population. On the other hand, we see smaller, highly developed European countries like Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway, which reacted quickly to COVID-19 and had shorter periods of reduced mobility. Another group of countries, including Finland, Japan, and Sweden, took longer to respond to the crisis but imposed shorter periods of reduced mobility. Finally, some countries like Serbia and South Korea had relatively short periods of reduced mobility compared to other countries.

The graph illustrates the grouping of countries based on their reaction time and duration of reduced mobility.

Spain is an outlier in this analysis, as it took a longer-than-average time to react to the crisis and has an undefined duration of reduced mobility, as there had not yet been an exact date for the return to normal levels. It seems likely that Spain's reduced mobility period was lengthy, similar to the other countries in group 1 – the “big European economies” of France, Germany, and Italy – which also had long response times and extended periods of reduced mobility. We thus assume that Spain is part of group 1.

With the different groups of European countries in mind, it is worth examining how the COVID-19 pandemic and the decisions made in response to it have affected people's interest in politics. Have the restrictions on daily life and the measures taken to address the crisis sparked a renewed interest in political engagement among the population, or have they led to disengagement and disillusionment with the political process? By exploring these questions, we can gain a better understanding of how the pandemic has shaped people's attitudes towards politics and the role it plays in their lives.

Has the COVID-19 pandemic increased people's interest in politics?

The Coronawiki dataset provides pageview data for various topics on Wikipedia over time, allowing us to track the evolution of interest in COVID-19 and politics during the pandemic. By examining the number of pageviews for these topics, we can gauge the level of interest and see how different stages of the pandemic have impacted it.

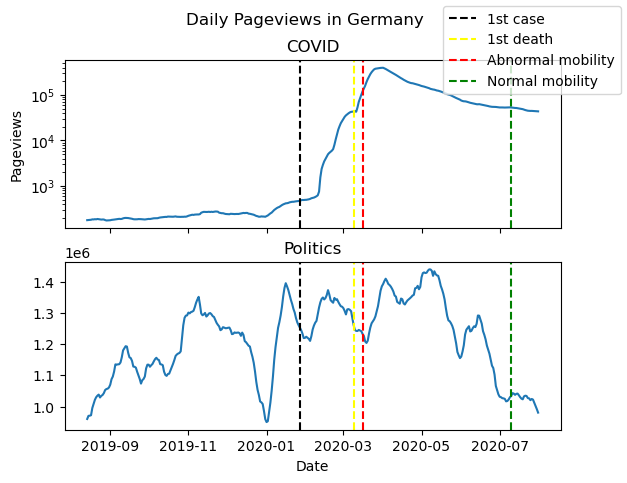

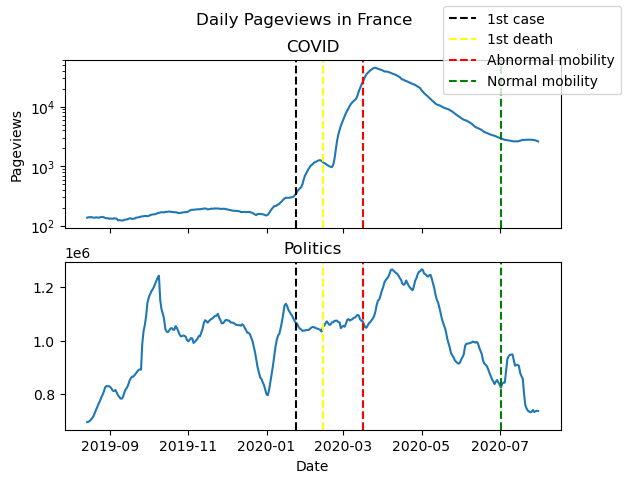

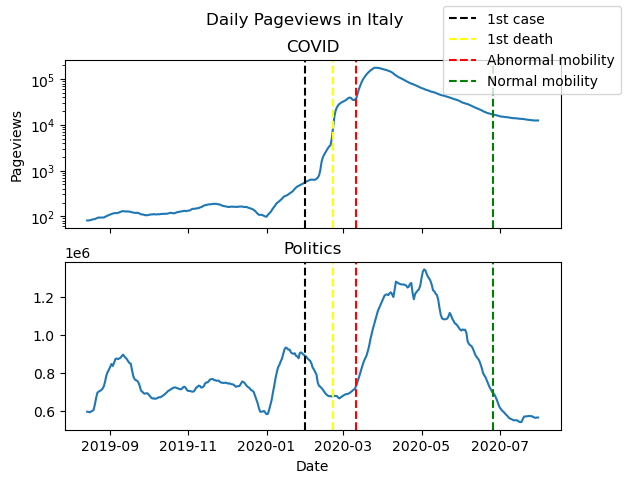

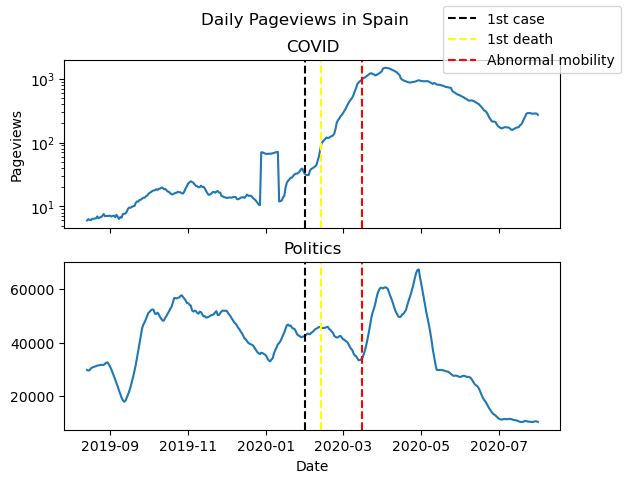

For four major European countries, we see that the rapid growth in interest in COVID-19 occurred around the time the first case of the virus was discovered in the country. This growth is steepest at the time of the first death or shortly thereafter, indicating that the news of mortality was a major driving force for increased interest. We also observe a peak in interest in COVID-19 in all four countries shortly after the beginning of abnormal mobility, coinciding with the implementation of lockdowns and other strict measures. As people's lives were disrupted and they had to adapt to a new way of living, interest in COVID-19 peaked.

There appeared to be no direct effect on the interest in politics when COVID-19 first appeared in these countries. However, we see a rise in interest in politics when mobility becomes abnormal, coinciding with significant decisions taken by governments to impose measures on the population. In addition, as people's mobility is affected, they may have more time to read up on politics, increasing political interest and awareness.

The figures display the pageviews for political and COVID-related pages over time for group 1 countries.

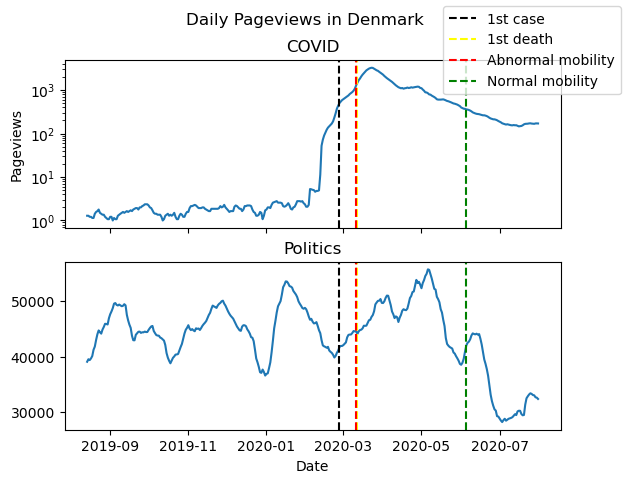

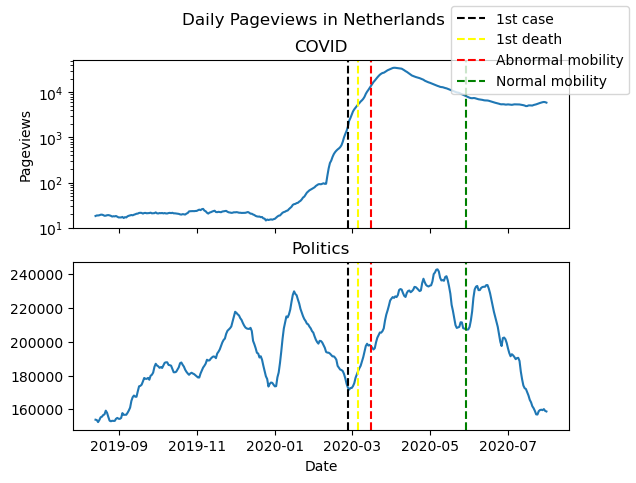

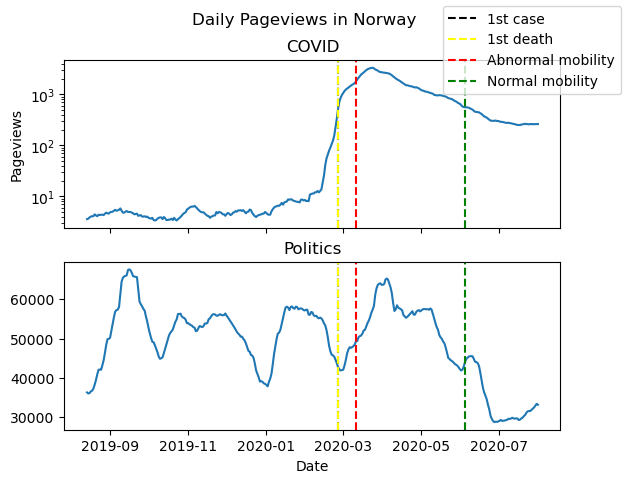

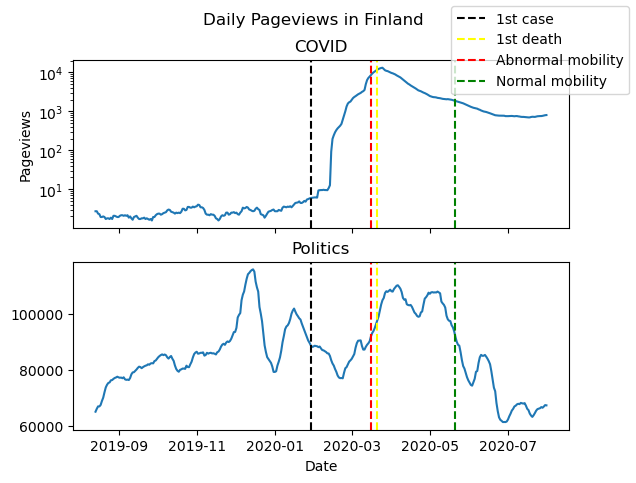

In smaller European countries that reacted quickly to COVID-19, we see a different trend in interest in COVID-19. The explosive growth in interest begins before there are even any cases of the virus in the country, which may be due to these countries closely monitoring the situation in the major European countries and being concerned about COVID-19 before it appeared in their own country. As a result, their governments quickly addressed citizens' concerns. These countries also show similar trends in interest in politics, with the first cases corresponding to the beginning of a rise in interest. However, unlike in the major European countries, interest in politics falls soon after mobility returns to normal.

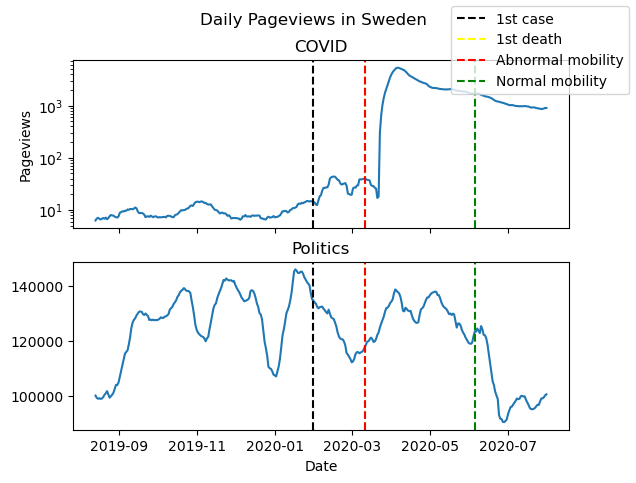

The figures display the pageviews for political and COVID-related pages over time for group 2 countries.

In the countries of group 3, measures to address COVID-19 were implemented relatively late after the virus arrived. Unlike the other two groups, the exponential growth in interest in COVID-19 had not yet begun when the first cases were discovered. The explosion in interest occurred roughly a week later in Finland, but in Sweden, it occurred approximately a month later, once mobility had begun to be affected. Sweden initially had very lax restrictions during the pandemic, and interest in COVID-19 did not initially surge. People only became interested in COVID-19 when restrictions started to impact their lives.

The figures display the pageviews for political and COVID-related pages over time for group 3 countries.

The arrival of COVID-19 did not significantly affect interest in politics in these countries, although some may have objected to the government's slow response. However, the populations in these countries were generally pleased with the initial response, as the ruling parties saw a boost in popularity. Interest in politics rose as measures were implemented and mobility became affected, but it quickly fell once mobility returned to normal.

Now that we have examined how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected interest in politics and how different countries responded to the crisis, we can turn to whether the population tended to support or disapprove of the leading political parties during this time. To answer this question, we can use polling data to see how people's views on the parties changed throughout the pandemic. This will help us understand whether the decisions made by the government were met with approval or backlash and how these views may have been influenced by the impact of the pandemic on people's lives and the measures taken to address it.

How did people's opinions of political parties change in response to COVID-19 interventions?

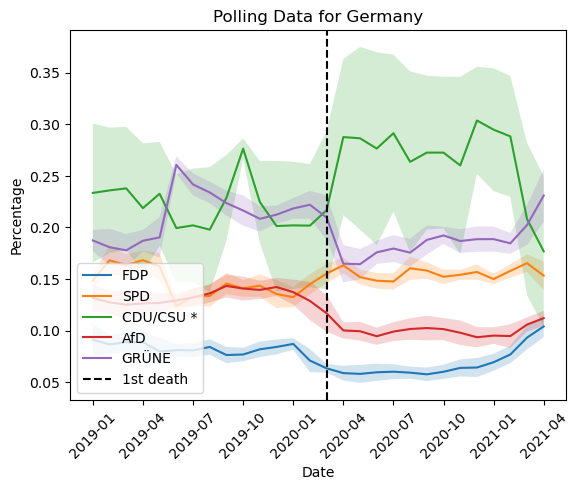

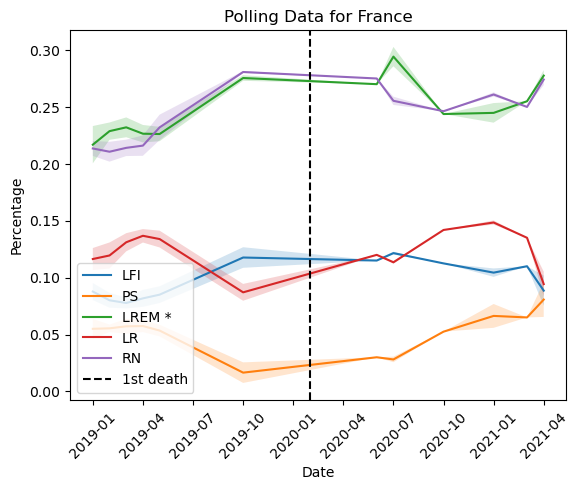

As we look at how the COVID-19 pandemic affected political opinions in different countries, we see that the populations in group 1 (large economies) had varied reactions. In Germany, there was a sharp rise in popularity for the ruling party, which may indicate support for their efforts to maintain stability and implement sanitary measures. In Spain, the main opposition party saw an increase in popularity. In Italy, a continual decrease in support for the main party in government began before the pandemic, suggesting that domestic issues were more influential on the party's popularity than the pandemic itself.

The following is the result of the polling for group 1 countries.

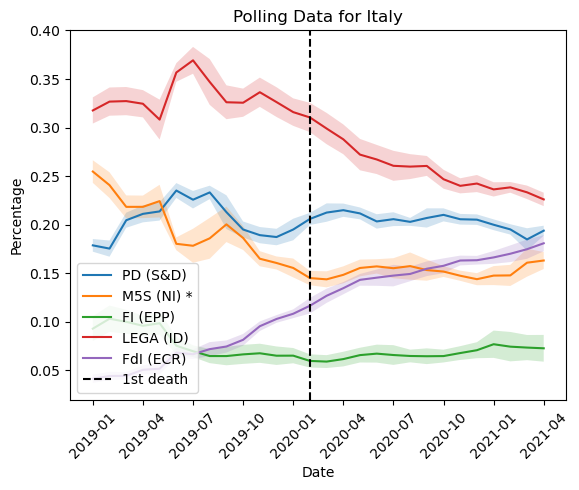

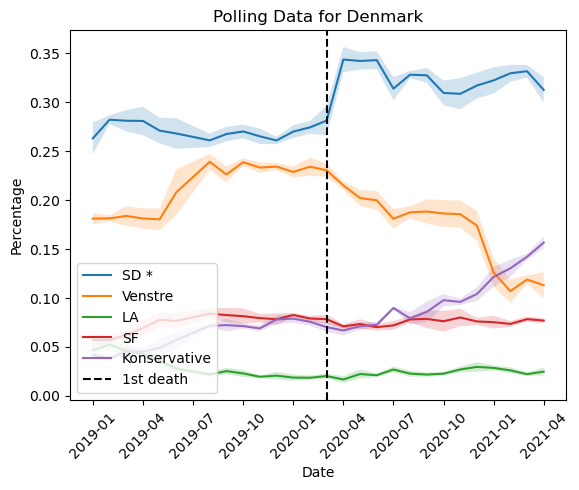

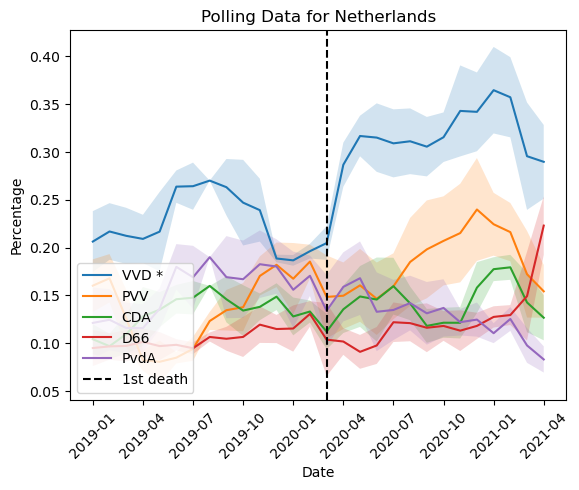

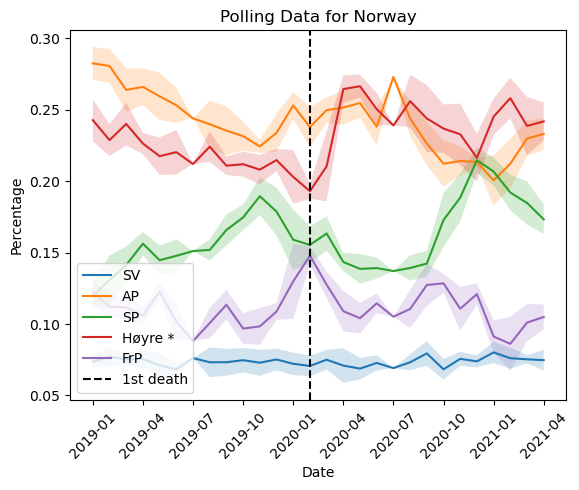

In contrast, the populations in group 2 (smaller countries where the government reacted quickly) all experienced sharp increases in support for the government. In Norway, the ruling party's steady decrease in popularity was almost entirely reversed, indicating that the population highly valued stability and appreciated the quick response of their government.

The following is the result of the polling for group 2 countries.

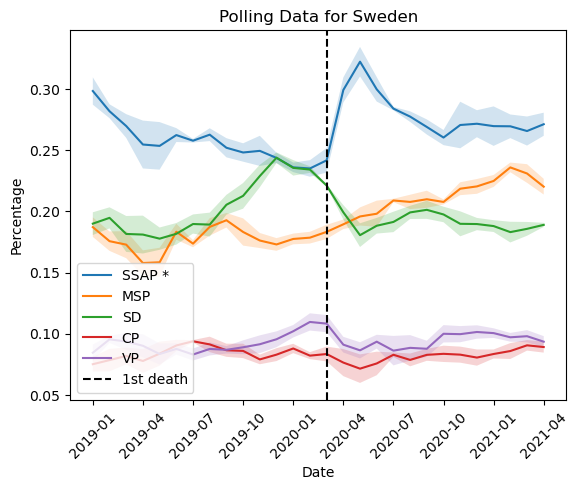

In group 3, we also see an increase in support for the government. It appears that, in smaller countries, governments saw an increase in support at the start of the pandemic.

The following is the result of the polling for group 3 countries.

To gather evidence to support our hypothesis, we conducted t-tests to see if there were statistically significant differences in the polling of ruling parties before and after the start of the pandemic in the smaller countries. We found statistically significant differences in the polling of the main ruling parties immediately before and after the pandemic's start. This allows us to reject the null hypothesis that no such difference exists.

A summary of the testing results is provided below.

| Denmark | Netherlands | Norway | Finland | Sweden |

| 0.00002 | 0.00212 | 0.00294 | 0.00017 | 0.00023 |

In times of crisis, it is common for people to rally around their leaders and offer support as they navigate the challenges. This is often due to a desire for stability and a belief that the government is best equipped to handle the crisis. In such times, people may be more forgiving of any mistakes or missteps previously made by the government, as they understand that addressing a crisis is not always straightforward and that leaders are doing their best to protect the population. Any potential change of leadership process would introduce another challenge to an already burdened government. Additionally, during a crisis, people may be more willing to comply with the measures implemented by the government as they understand that such measures are necessary to protect public health and safety. As a result, we often see an increase in support for the government during times of crisis. This is the case in the smaller countries in our study, where governments saw an increase in support at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Have the COVID-19 pandemic and the decisions made by governments impacted people's views of politics and political parties? Our analysis has shown that in some cases, the actions of governments did not align with the reactions of their population, mainly regarding mobility reduction. We also identified different groups of countries based on their response to the pandemic, which may be influenced by factors such as population size and the severity of the crisis. The pandemic also sparked an increased interest in politics as people sought to understand the decisions being made by their governments and how they would be affected. Additionally, we found that people tend to support their ruling political parties during times of crisis, as they look to their leaders for stability and guidance. Further research is needed to fully understand the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on political opinions and behaviours.

Further Work

As the COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered people's views and behaviours, it raises the question of whether these changes will persist in the long term. Will the population continue to align with political decisions, or will there be shifts in attitudes and actions as the crisis evolves and becomes resolved? Examining this question through a study over a longer duration and through each wave of the pandemic could provide valuable insights into the ways in which the population may respond to political decisions and events in the future. Understanding the lasting effects of the pandemic on politics will be important for predicting and navigating the changing landscape of the political sphere.